All genealogists have a fantasy list of the ancestors they would most like to have a conversation with, usually in the hope of unearthing some vital piece of missing information. Although there are several such people on my own list, my maternal grandfather, William Jack Cullingford, would be at the top as the stories I would most like to hear are those that concern his 30 years in the Royal Navy, which included active service during both World Wars. Sadly, he died when I was a small child, so I never got the opportunity, and I have instead had to piece together his life at sea from his service record and the second hand recollections of my grandmother.

Always known as Jack, grandad was born on 22 October 1899 in Wantisden, Suffolk. No doubt the expectation was that he would spend his life working on the same farm as several generations of his family but in June 1916, at the age of 16, he ran away from home to join the Royal Navy. The photograph below dates from around 1919 and is carefully posed to show off the war service chevrons on his right sleeve.

William Jack Cullingford c 1919

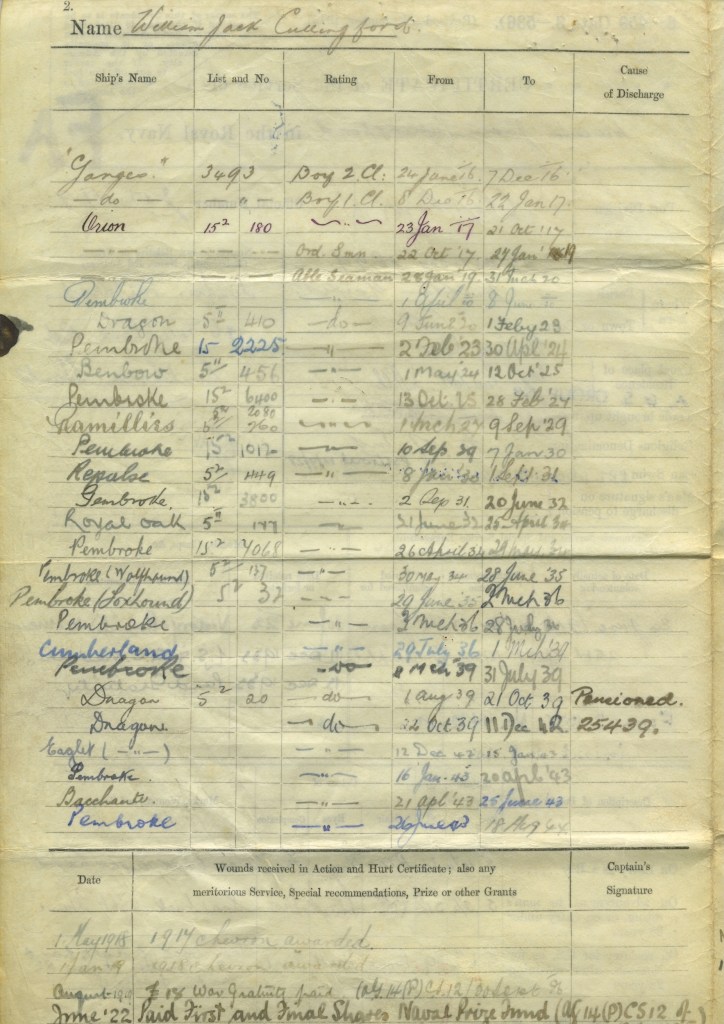

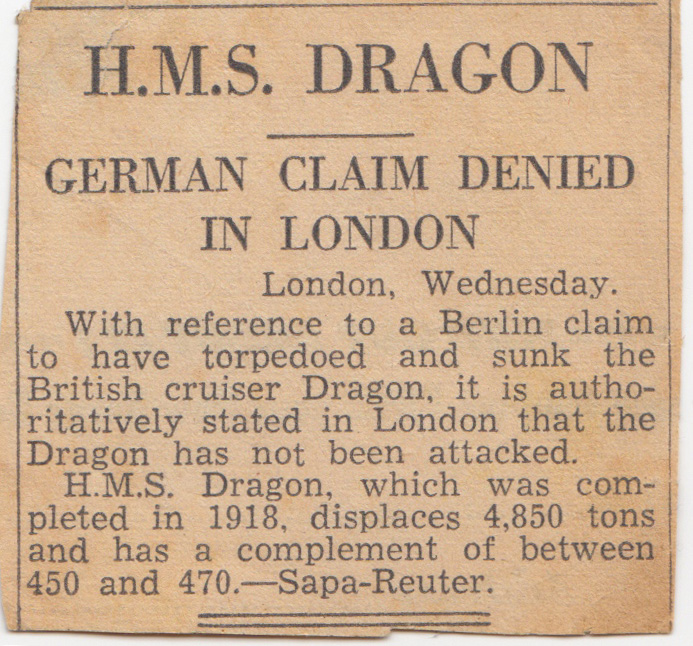

Jack’s service record (pictured below) shows that, initially, he was sent to HMS Ganges, which was a shore-based training establishment in Shotley, Suffolk. Named after a 19th century sailing warship, the training at Ganges is generally described as “uncompromising” in its aim to transform “boys into men” fit to serve in the fleet. A notorious feature was the requirement to climb at least part way up the 142 foot-high ship’s mast which stood on the parade ground. On ceremonial occasions this would be “manned” by a team of boys standing along the spars and hanging from the rigging – my grandfather clearly had a head for heights as he became the “button boy” who stood on the 12 inch diameter platform at the very top, with just a short lightning conductor rod for a handhold.

Extract from the Royal Navy Service Record for William Jack Cullingford

After completing his training, Jack’s first posting was to HMS Orion, a dreadnought battleship launched in 1910, which he joined on 27 January 1917. Although Orion had been involved in the Battle of Jutland the previous year, in common with the rest of the British fleet she spent the remainder of the war on routine patrols and training exercises in the North Sea as the German navy had retreated to the safety of their home port.

Jack was, however, to witness the extraordinary sight of the surrender of the entire German High Seas fleet, which took place in the Firth of Forth on 21 November 1918. Said to be the largest ever gathering of warships, Orion was one of almost 200 British battleships, cruisers and destroyers who sailed out to form an escort for the 70 German ships that were to be interred at Scapa Flow under the terms of the Armistice.

Orion was the flagship for the Second Battle Squadron from 1916 – 1919 under the command of Admiral Sir William Edmund Goodenough, who had been captain of HMS Southampton at Jutland. My grandmother used to tell me that my grandfather had acted as cabin boy to an admiral at the battle, which clearly cannot be correct given the date he enlisted, but it is entirely possible that he did hold this position in the later stages of the war.

It seems very wrong to gloss over the next 20 years of my grandfather’s service, but time and the theme for this post means that reluctantly I must do so. His shore base was HMS Pembroke in Chatham, where he was stationed between the overseas voyages that lasted up to two and a half years. Much of his early inter-war service was spent aboard ships that were part of the Mediterranean Fleet, but his time on HMS Cumberland took him to the China Station, which had been established to protect British interests in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. During this time, he had a range of roles including acting as the ships’ diver, who was responsible for checking the hull for mines, and operating the catapult used to launch spotter planes.

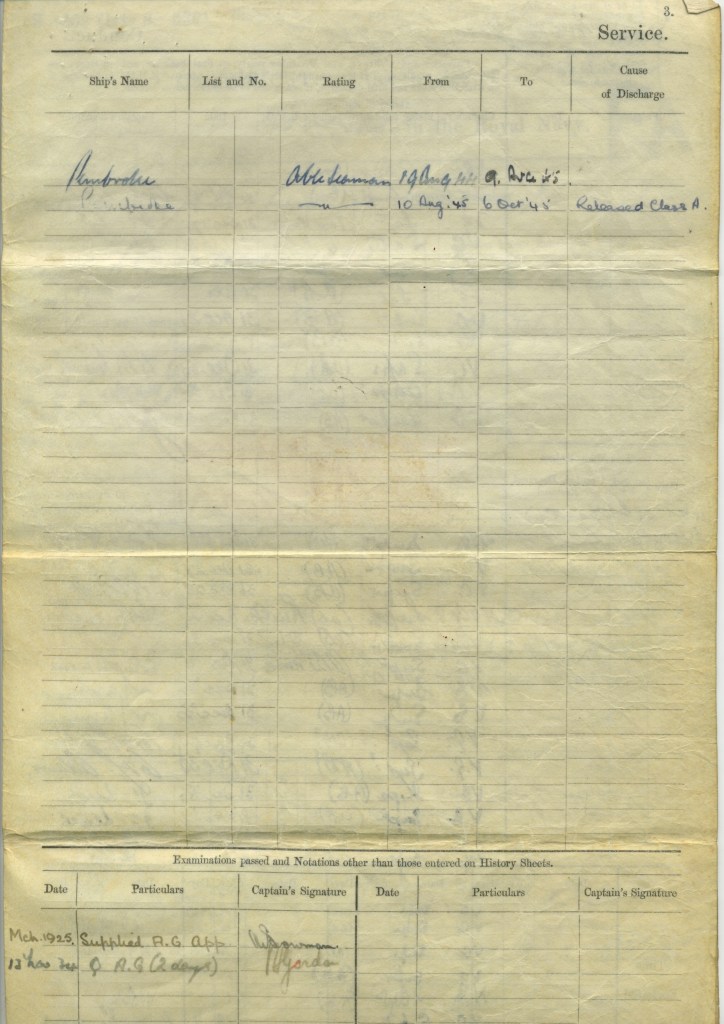

When war was again declared on 1 September 1939, my grandfather had just joined HMS Dragon, a light cruiser dating from 1917 which he had previously served on in the 1920s. The newspaper article below is dated the same day as Jack joined the ship, so it seems that initially he was engaged in training the reservists as a member of the skeleton crew. In all 12,000 civilian sailors had been called up for training and to ready ships from the Reserve Fleet for active service.

Daily Mirror 1 August 1939 [Source: British Newspaper Archive]

On 21 October 1939, Jack completed the years of service required to draw a Navy pension, but he reenlisted the following day and was aboard Dragon when she joined the 7th Cruiser Squadron in Scapa Flow, Orkney, where her role was to blockade German ports and prevent her warships from leaving the North Sea.

On 12 October 1939, the Squadron was dispersed due to concerns that an air attack was imminent, apart from the Royal Oak, which remained at anchor in Scapa Flow as she was damaged. Two days later she was hit by several torpedoes fired from a German U-boat and sank with the loss of 835 sailors, 134 of whom were not yet 18 years old. This was a massive blow to morale for a country that had long prided itself on the dominance of its navy and the news must have been particularly sobering for Dragon’s crew as they had been on patrol with the Royal Oak just a few days earlier. Some, including Jack, had actually served aboard her.

As one of the older ships in the fleet, Dragon was soon found to be unsuitable for service in the North Sea weather conditions and was transferred to the Mediterranean after taking part in the hunt for the infamous Graf Spee battleship in the Atlantic. The first action she saw was during Operation Menace, which was an unsuccessful attempt in September 1940 to capture the strategic port of Dakar in a bid to replace the Vichy administration with the Free French under General de Gaulle.

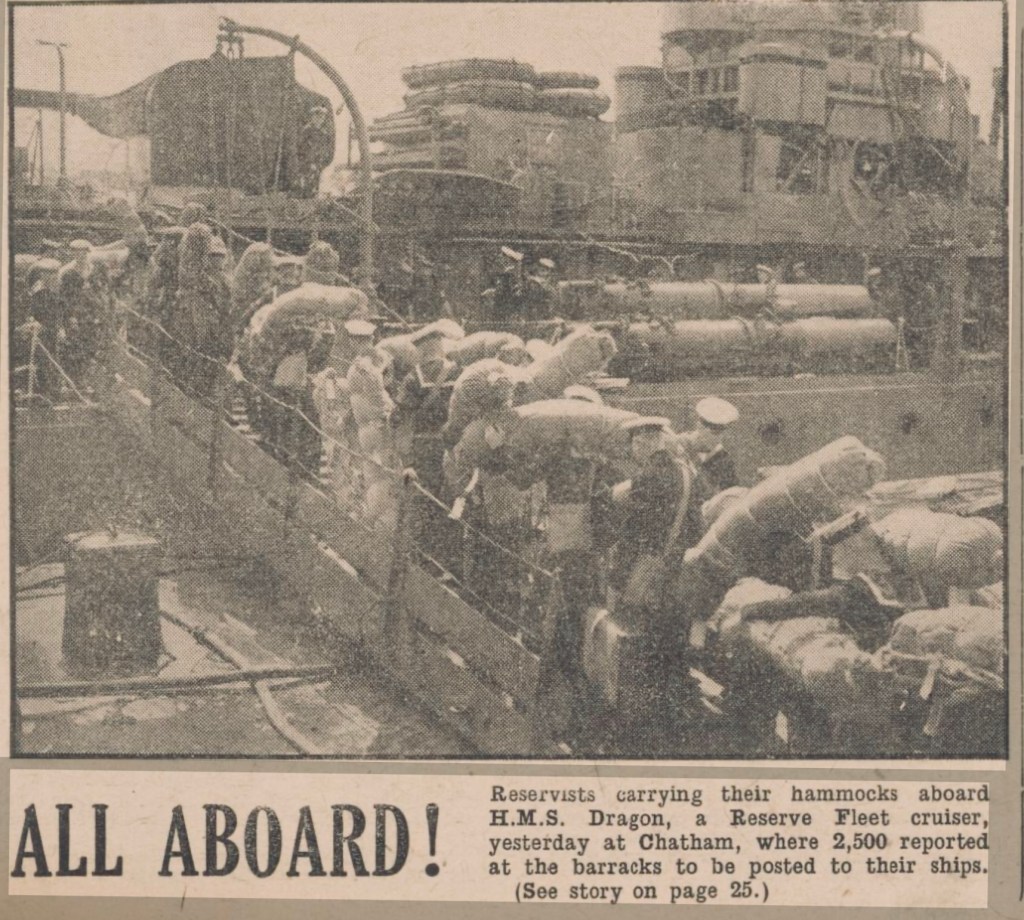

For most of 1941, Dragon escorted Atlantic convoys of merchant ships bringing vital supplies of food, equipment and raw materials to Britain. In November that year, the Nazi war propaganda machine gave my grandmother some sleepless nights when they claimed in a radio broadcast to have torpedoed and sunk her, forcing the Ministry of Information to issue a denial. My grandfather was apparently wholly unsympathetic and remarked that it was her own fault for listening to Lord Haw Haw.

At the end of that year, the ship was moved to the Indian Ocean to became part of the Eastern Fleet based in Singapore and deployed to escort military convoys. This was effectively a token force made up of older ships as the Royal Navy’s focus was on keeping the Atlantic sea-lanes open. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941, the war in the Pacific rapidly escalated and the vulnerability of the Eastern Fleet was all too soon exposed.

On the day after Pearl Harbour was attacked, the crew of the Dragon watched as Force Z, comprising the modern battleship HMS Prince of Wales, HMS Repulse (which Jack had served on 10 years earlier), and four destroyers set sail to engage with the Japanese, who were carrying out amphibious landings on Malaya. Two days later, the shocking news would reach them that both the Prince of Wales and Repulse had been sunk by enemy aircraft. They were the first capital ships moving at sea to be sunk in this way and the loss of 842 men made it one of the worst disasters in British naval history.

At the beginning of 1942, Jack took part in the desperate last minute evacuation of civilians and service personnel as Singapore was invaded by the Japanese and Dragon is reputed to have been the last ship to leave the city before it surrendered on 15 February. Faced with an opponent that possessed a far superior striking force, the Eastern Fleet retreated to Java in the knowledge that most of its ships were approaching obsolescence and, crucially, lacked sufficient air support.

The Commander of the Fleet, Admiral Somerville, divided his ships into two divisions based on their capability and, as one of the older and slower ships, Dragon was assigned to Force B whose role was escorting convoys rather than direct action against the Japanese. She also took part in unsuccessful searches for invasion craft during the Battle of Java and, after the island fell on 28 February 1942, moved with the Eastern Fleet to Colombo in Ceylon.

On 1 April 1942, in anticipation of a raid on Ceylon, Force A were deployed in an attempt to locate and intercept the enemy ships, with Force B positioned 20 miles to the west as it was considered too risky for them to remain in port. The hunt continued for several days, during which HMS Cornwall and HMS Dorsetshire, who had been detached from the rest of the fleet, were both spotted and sunk.

It was now clear that the Eastern Fleet stood no chance of survival in an engagement with the Japanese and, after a conference with his commanding officers, Admiral Somerville decided it was crucial to preserve the remainder of his Fleet in order to protect the vital convoy and troop ship movements. On 8 April, Dragon and the rest of Force B was therefore sent to Kilidini in Kenya where they would be safe from air attack.

During April and May, Dragon escorted military convoys in the Indian Ocean, including those carrying troops bound for Operation Ironclad, which eventually led to the capture of the strategically important island of Madagascar from the French Vichy forces. By June, however, she was under repair at Simonstown, South Africa and in July 1942 she was withdrawn from operational service, with most of the crew landed and moved to other units.

The problem was now how to get Dragon, with Jack amongst her skeleton crew, back to Britain for refurbishment and it would be several months later when she finally arrived in Liverpool having been attached to a succession of convoys.

HMS Dragon was to be the last of Jack’s postings at sea as the remainder of his Royal Navy service was spent at shore bases in Chatham (Pembroke), Liverpool (Eaglet) and Aberdeen (Bacchante). He was finally released from service on 6 October 1945, a month after the Japanese surrender ended the war. Sadly, the ending was a less happy one for Dragon as, after supporting the D-day landings, she was damaged by a torpedo and scuttled to form part of the artificial breakwater at Courseulles-sur-Mer.

Jack’s connection with the Navy was not quite at an end, however, as he secured work as a rigger in the Royal Dockyard in Portsmouth. This was a skilled job which involved the movement and control of ships using ropes, pulleys and winches. His familiarity with more traditional rigging and masts, gained during his training at HMS Ganges, did still come in useful on occasion, however.

In the late 1940s, he was one of the team who put the rigging back on HMS Victory, which took several months and around 26 miles of rope – in the photograph below, he is standing fourth from the right in the second row.

The team of men who re-rigged the Victory after WWII

And then, in 1951, he became a film extra in Captain Horatio Hornblower when the call went out for men who could scale the rigging. I have no idea if he ever met leading man Gregory Peck, but he did apparently frighten all the neighbours when he arrived home wearing his film make-up and a pigtail.