It would be a rare genealogist who does not enjoy exploring a cemetery, and I have visited many over the years. There is always the hope that the inscription on a headstone will reveal some missing detail of an ancestor’s life, but mostly I just enjoy the feeling of being in a place that would have meant a great deal to them.

Sadly, in most cases I have found it impossible to work out the precise location of a family member’s grave and even when I have been able to, it is rare for there to be a headstone as they were beyond the means of poorer families and, where they did exist, time has often eroded the inscription to the point where it is illegible .

It was therefore a particularly pleasant surprise to come across this fine granite memorial in the Constitution Street Cemetery, Peterhead which marks the resting place of my great great grandmother, Christian Clark, who is buried in a family lair with members of her daughter’s family.

I’m not sure that it is good genealogical practice to have a favourite ancestor, but Christian is certainly the one that I most admire for the resilience she showed in the face of great adversity. Previous blog posts relating to her husband and son have already provided some insight into the predicament she found herself in, but I think that this remarkable woman deserves a tribute of her own so some of the details from those earlier posts will be repeated here.

There is no record of Christian’s birth or baptism, but according to her death certificate and the census returns, she was born in Fraserburgh in about 1806 to parents James Clark and Isabella Forman, who had married in Longside on 13 July 1793. James was a farmer, and records suggest that Christian had six older siblings:

James Clark – born 1793 in Rathen

Sarah Clark – born 1794 in Longside

Bathia Clark – born 1796 in Longside

Mary Clark – born 1799 in Fraserburgh

Isobel Clark – born 1801 in Fraserburgh

Charles Clark – born 1802 in Fraserburgh

Christian married William Clark in Fraserburgh on 18 May 1834 and so far as I can tell they were not closely related despite sharing a surname. It seems that she may have been as much as 10 years older than her husband, which would have been very unusual for the time – William’s age is given as 25 in the 1841 census when Christian would have been around 35 years old. At that time William was a crofter and the family lived at Longhill, Lonmay, which then comprised a series of small crofts strung out along one side of the road between Mintlaw and Fraserburgh.

Analysis of the census record reveals many interrelationships between the inhabitants of Longhill, so it seems to have been a close-knit community. None of the original houses survive, but they are likely to have been simple single storey, two-room dwellings built from the local granite with a turf or heather roof.

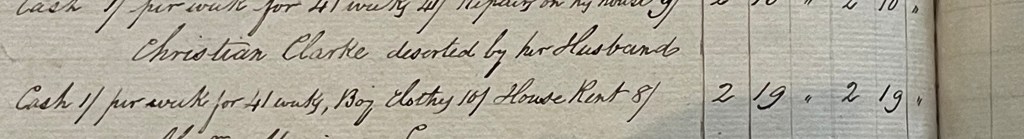

The Clarks had three children – Margaret (1835), John (1838) and William (1842) but the marriage was not destined to last as a list of Paupers in the Parochial Board Minutes for Lonmay reveal that by 1845 Christian was deemed to have been deserted by her husband:

Extract from the Lonmay Parochial Board minutes, 1845

These must have been desperate times for Christian and the Parochial Board minutes reveal that she continued to need regular financial support for the next 10 years. There are enough clues in the minutes, including a birth year and address, to confirm that these records relate to my great great grandmother.

In 1851, Christian is recorded simply as Mrs Clark, a pauper living at 4 East Row, New Leeds, Strichen – although technically in a different Parish, in practice this would have meant a move of no more than a few hundred yards from the Longhill croft. Two of her children, Margaret and William, are living with her while eldest son John is working as a cattleman on a nearby farm. Alongside “pauper” Christian’s occupation is described as “out and indoor labourer” suggesting that she was picking up casual work – as an able bodied adult she would have been expected to work whenever possible and by this time the Parochial Board minutes show that she was only receiving payment for her rent rather than the additional weekly allowance they had provided when her children were younger.

New Leeds had been founded in the late 18th century by Captain Fraser, son of the 8th Lord of Strichen, with the somewhat over ambitious goal of rivalling the textile industry in the Yorkshire city from which it takes its name. The success of the venture can be judged from the description in the Ordnance Survey name book from around 1870: “applies to a small miserable looking cluster of houses in which is a school and post office close to the main road leading from Aberdeen to Fraserburgh”.

Built on poor, boggy land that was notoriously a haunt for thieves, poachers and smugglers, New Leeds quickly acquired a reputation for housing misfits and the displaced – by the time of the 1851 census it is clear that it was a far from prosperous place with 22% of the population retired or paupers and most of the remainder working as crofters or agricultural labourers. It is notable that Christian describes herself as a “wife” in the census rather than head of household, perhaps suggesting that she expected to be reunited with her husband eventually.

The above image shows houses in the road that was formerly named East Row, which I visited earlier this year. New Leeds is now a popular commuter village and, although these original buildings give an idea of the sort of house Christian would have inhabited, modern living standards clearly bear no relation to the poor conditions that she endured in the mid-19th century.

How Christian eventually managed to pull herself out of poverty is unknown, but by 1855 the Parochial Board has decided that the family can now support themselves and in 1861 she is living at 34 Longate, Peterhead with daughter Margaret, son William and Margaret’s daughter, Helen Ann Milne. Christian’s occupation is described as a grocer, which is how she makes her living for the rest of her life.

Although clearly an improvement in economic circumstances, Longate was not the most salubrious part of town with regular newspaper reports throughout the 1850s calling for drainage to replace the open sewer which ran down the street – in 1861 “of all the streets in Peterhead, Longate is the most filthy, and is likely ever so to remain” and it is not until 1863 that drains are finally laid.

Longate was redeveloped in the mid-20th century, so the building Christian lived in no longer exists. Old maps and air photographs reveal that originally the street was lined with small, densely packed two and three storey buildings, and newspaper advertisements suggest that there were a wide range of small businesses operating from them. It is likely that Christain’s shop was in the front room of the building and that the family lived upstairs – the 1861 census describes No. 34 as having three rooms with windows, which actually compares favourably with most of the neighbours who had just one or two.

Christian is still living in Longate with Margaret and her family in 1871, but in this census she describes herself as a widow for the first time. Had she received information that William had died or was she simply tired of saving face having been deserted by her husband so many years before ?

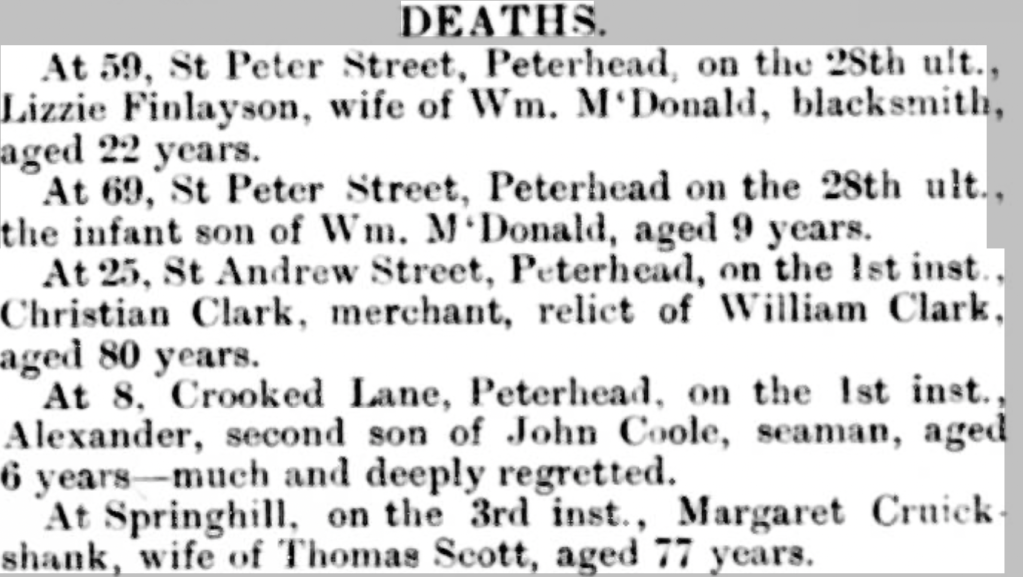

By 1881, Christian and her daughter had moved to 25 St Andrew Street, Peterhead, and that is where she died on 1 November 1885 at the age of 80. The announcement of her death describes her as the relict [widow] of William Clark despite the fact that they had lived separately for most of their marriage.

Extract from the Peterhead Sentinel, 4 November 1885

Source: The British Newspaper Archive